News

How to stop informal health care providers performing Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C)

To recognise this year’s World Health Day, we speak to Millicent Onyenuche from Circuit Pointe, a non-profit, youth-led organisation established in 2015 by a young female Nigerian after hearing untold stories of oppressed women, abused teens and victims of traditional practices. The organisations 2-year project in Nigeria looks to end Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C). It is funded through the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs’, Supporting civil society action and movements to end female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) program.

The project aims to support 40 Traditional Birth Attendants to abandon the practice of FGM/C, helping them to transition to an alternative livelihood.

What is FGM/C?

Female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C) is a permanent and harmful procedure involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. It is a violation of girls’ and women’s fundamental human rights and can lead to life-long damage to the female body. Approximately 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM/C, over two-thirds are from the African continent. Nigeria, where over 20 million girls have undergone FGM/C, accounts for approximately 10% of the global total of cases.

In South-East Nigeria, most girls undergo FGM/C before they are 10 days old. The procedure is performed by a ‘Traditional Birth Attendant’ (TBA), at the request of a family member. The TBA also provides an at-home child delivery service to pregnant women and nursing mothers.

We recognised that TBAs were the group most likely to obstruct the success of our project. Not only for cultural reasons, but also because of the economical and status benefits they gained through their role. TBAs are known and respected for their work and can charge about N4,000 to carry out FGM/C on a child.

The challenge was getting TBAs who are known and respected for their handiwork to abandon FGM/C during our 2-year project timeframe.

How did you approach this challenge?

We began by building our knowledge of TBAs. Working with the project communities, we carried out a TBA identification and mapping exercise. Not only did this allow us to leverage the community’s knowledge to help us identify TBAs, but it also allowed the communities to demonstrate their readiness and willingness to abandon the practice of FGM/C.

We were able to identify 60 TBAs per state – both active and inactive – and connected with them via our community network. They were invited to discussion forums through key community influencers who we had already built partnerships with, like Executives of Women Associations or religious leaders of the churches that they attended, and even through their daughters who were part of the youth associations working with us.

At the discussion forums the 40 TBAs who attended were split into smaller groups to enable us to have in-depth conversations and share knowledge and insight. We held four interactive sessions and each session had its own objective.

- Session 1: To understand why the TBAs perpetuate the practice of FGM/C

- Session 2: To make the TBAs aware of the health, physical and psychological consequences of the practice of FGM/C as well as the legal implications of their actions

- Session 3: To collate reactions, comments, suggestions, proposed alternative means of livelihood

- Session 4: To encourage the TBAs reach an individual choice to abandon FGM/C and to make a collective decision on alternative trades.

What was the result?

Overall, we’ve recorded that the 40 Traditional Birth Attendants have collectively influenced over 300 families to abandon FGM/C because they had stopped performing the practice!

After the discussion forums, the TBAs gradually recognised the negative impact of their actions as FGM/C practitioners. Although these TBAs viewed the practice of FGM/C as a source of income and felt they were helping their fellow women, as they got more knowledge on the issues relating to FGM/C, they realised the implication of their actions. Two key drivers for their abandonment of FGM/C were the recognition of impact on the future of the female baby and the legal implications of their actions.

“I had the intention of training my daughter to become a TBA so she can continue my handiwork but since I have heard about the complications of FGM, I will not teach them again.” Participant

"After hearing the implications of FGM, I have joined others to spread the information against FGM in schools, churches & markets."

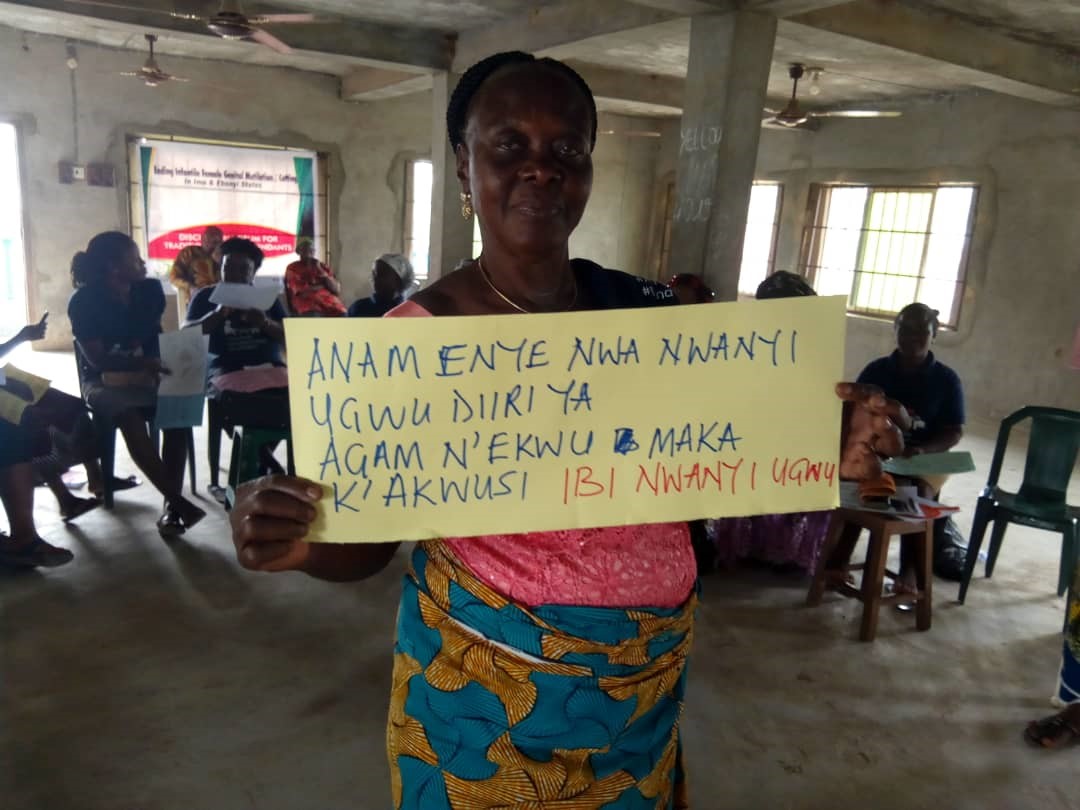

The TBAs demonstrated their readiness to abandon the practice of FGM by making individual pledges. Following the logic that social norm change is most effective when people see or believe that others are also changing, we created a safe space where 36 TBAs gathered, wrote their affirmations as simple decals and said them out loud in the presence of others.

Photographs from the TBAs training programme

It was clear that each TBA was disturbed by what they learnt about the impacts of FGM/C. Some reflected on harm they may have caused over the years, many worried about how they could possibly learn a new trade at their age, while some argued and insisted that FGM/C should not be stopped but should be a choice which girls can make when they reach decision-making age.

To help find alternative incomes we proposed small scale businesses to the TBAs. The group committed to participating in a 3-month training programme on alternative means of livelihood, this strengthened their commitment to abandon their role as FGM/C practitioners.

Photographs from the TBAs training programme

Visits to the TBAs took place after their pledges to abandon FGM/C. Many showed off their new trades. During their interviews, 20 TBAs in Ebonyi State were asked if they had the urge to go back to performing FGM/C, we received a strong "no". 100% of the TBAs said they made more money now and can feed their family and feel good about what they do.

What would your top project tips be for other organisations?

Collect data: A good place to start is within local communities. Gather as much information as you can and build profiles of your key stakeholders. Within our project, our engagement with the community allowed us to identify TBAs and ensured our future engagement with the TBA community was from an informed point of view.

Build bridges: Find out which groups of people have an influence on the community you are trying to impact. This could be family members, pastors or a tribal/traditional ruler.

Work from within: Find people who are already positioned in the lives of community members and engage them as change agents who can help accelerate your cause. In our project, the TBAs were the change agents and they were able to help accelerate the FGM/C abandonment process.

Create win-wins: Identify why communities are engaging in the behaviour that you are trying to change so that alternative options can be offered. We found that TBAs felt excluded from the system of child delivery due to increasing presence of medical facilities and professionals in rural areas so they focused more performing FGM to make ends meet. Offering them an alternative means of livelihood accelerated their decision to abandon the practice and created win-wins.

Support Commitments: Ensure that you maintain a relationship with your target communities even after you have finished your project activities. Send an SMS, organised a follow up call or set up an annual focus group discussion.